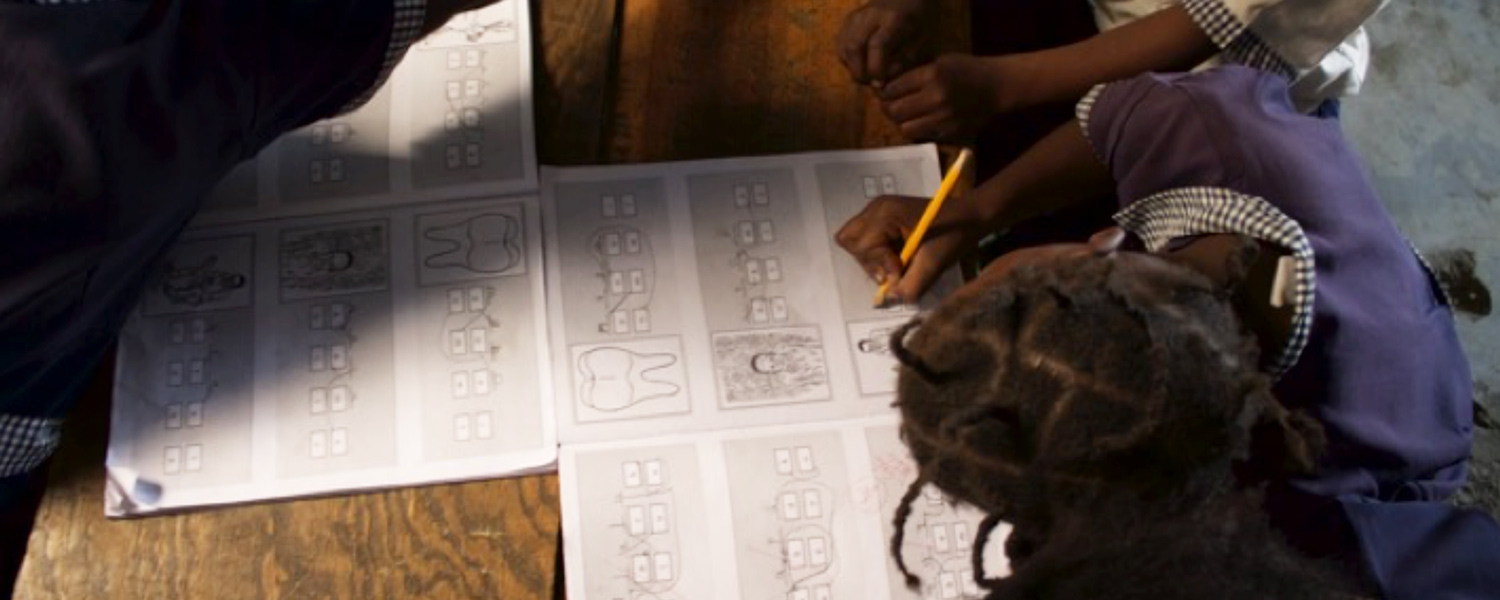

Zambian students use Vernacular, a tablet-based literacy intervention created by EDC.

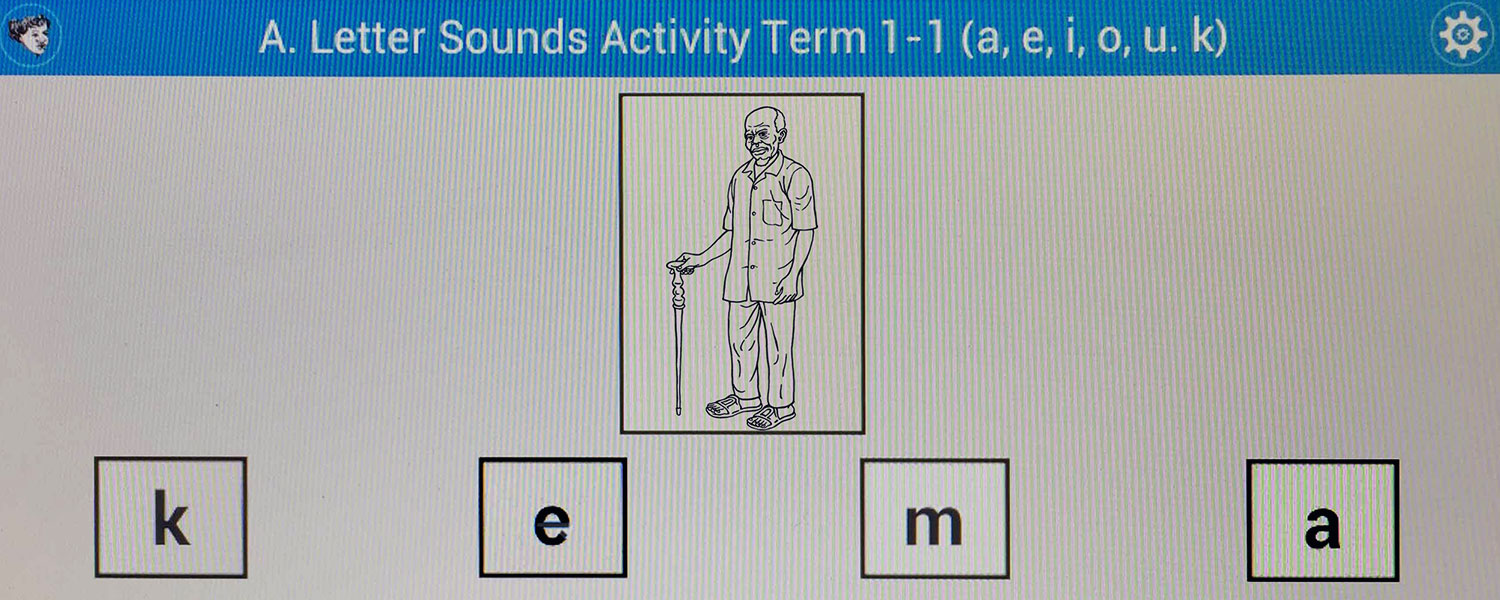

Three 7-year-olds cluster around a small Android tablet at Chartonel Community School in Lusaka, Zambia. A drawing of a woman’s purse and the letters k, p, u, and c are displayed on the screen. Their job? Find the letter that corresponds to the initial sound of the word cola, which means bag or purse in the local language of Cinyanja.

One student taps c. Success! The answer is correct, and the black and white silhouette fills with color. Smiles abound. A new word appears, along with four new letters.

This moment is remarkable considering where it is taking place. Chartonel is a community school—created and maintained by local parents who cannot afford the fees for their children to attend government-run schools. When school lets out, most of these children will return to homes with no electricity. Few have ever used a tablet outside of this classroom.

But the success of the tablet-based program here—as well as at nine other community schools around Lusaka—is proving the tremendous power of technology to boost literacy learning in some of the poorest, most remote communities in Africa.

EDC’s Simon Richmond led the development of this USAID-funded literacy intervention called Vernacular. Vernacular is an interactive, tablet-based program that asks students to match letters, sounds, and pictures—all tasks that reinforce letter identification, phonemic awareness, and basic reading skills in Cinyanja, the students’ mother tongue.

“Vernacular gives children the opportunity to practice basic reading skills, while giving them the immediate feedback that they often do not get from the teacher,” says Richmond. “Ultimately, we want to help the teacher improve her skills. Vernacular is a fantastic activity in the meantime.”

Richmond sees great potential for Vernacular. First of all, there’s tremendous need. A 2016 EDC survey revealed that 66 percent of second-grade students in Zambian community schools where Vernacular was used could not provide the correct sound for a single letter, and 84 percent could not read a single word. Second, educators have long held that individualized, immediate feedback is critical to helping young children learn how to read—feedback that is often absent in community school classrooms but which Vernacular provides.

“When you consider the long-term learning gains afforded by technology, it’s actually a better investment than workbooks.” –Stefan McLetchie

New research shows just how much of an impact Vernacular can have. Zambian students who used Vernacular during the four-month pilot consistently outperformed students who used a workbook literacy intervention. On one decoding task, the Vernacular group performed four times as well as the workbook group, and similar results were found on a reading fluency task. Students who used Vernacular also scored better on reading comprehension tasks—even though improving reading comprehension skills was not a specific focus of the Vernacular activities.

“Improvements on higher order reading skills are really hard to get,” says Richmond. “So if we are seeing these improvements after only four months, then we are really onto something.”

A simple interface makes Vernacular easy to use—and easy to code.

Vernacular is so notable because it addresses a number of barriers that have, historically, prevented technology interventions from being adopted at scale in low-resource communities. One is the idea that tablet-based interventions are simply too expensive.

At first look, Vernacular does seem more expensive than the paper-based alternative. The tablets needed to run Vernacular currently sell for about $40 each, and schools also need a charging station to power the tablets. By contrast, each student workbook costs only $0.88 to produce.

But Stefan McLetchie, chief of party for EDC’s work in Zambia, says that Vernacular becomes cost effective when you examine the cost of achieving specific student learning gains. To calculate this cost, he divided the per-student cost of each intervention by the effect size of students’ literacy improvement in each condition. The result? Over the course of one year, a $44 investment in workbooks would have the same impact on improving students’ decoding skills as a $27 investment in Vernacular-programmed tablets.

Even after extending the calculations to three years, and factoring in the costs of replacing some tablets versus printing new workbooks each year, Vernacular continued to deliver more results, at a lesser cost, because of its strong impact on student learning. McLetchie estimates that over a three-year period, every $2.20 spent on tablets could have the same impact on literacy learning as $14.60 spent on workbooks.

“When you consider the long-term learning gains afforded by technology, it’s actually a better investment than workbooks,” says McLetchie.

EDC research suggests that Vernacular was more effective than a similar, worksheet-based intervention.

Another barrier is language. Zambia alone has seven related, but distinct, Bantu-based languages in use across the country. Reaching scale requires building content for every one of them.

Vernacular solves this problem through the simplicity of its back-end design. To customize the program for a new language, an educator only has to create and insert new audio and image files within an easy-to-use interface. (EDC also created that interface, called Stepping Stone.).

“We wanted to build a software engine that could be deployed in multiple mother tongues, and that relied on local talent to record sounds, draw images, and ultimately assemble the program,” says McLetchie. “And that’s what we have been able to do.”

McLetchie is hopeful that Vernacular can be scaled up and used in other countries across sub-Saharan Africa. Many of the issues that the project confronted in Zambia—such as large class sizes, low literacy rates, and multiple mother-tongue languages—are also present throughout the region. Vernacular could be an essential tool in improving literacy for millions.

“Vernacular provided us with an opportunity to test a new technology and to ask, does it work? Is it cost effective?” he says. “We found that even in some of the most marginalized schools in Zambia, the gains were so great that it is worth the investment. It’s a really promising model.”