A Second Chance at School in Mali

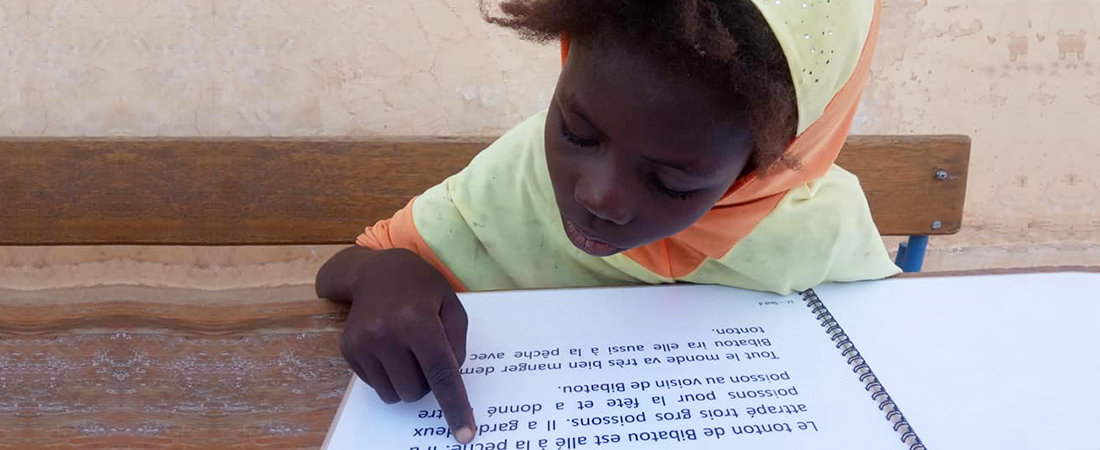

In 2012, a political coup in Mali led to the temporary closing of most schools in the northern part of the country. Mariam Ibrahim, then only six years old, was among those affected. For the next few years, Mariam—who had been attending a religious school in the Gao region—stayed home and performed domestic chores at a time when she should have been learning how to read and write.

Then in 2017, Mariam’s parents learned about a program that was providing out-of-school youth with a second chance at an education: EDC’s USAID-funded Education Recovery Support Activity (ERSA). ERSA offers intensive, accelerated education (AE) programs that give children the basic literacy and mathematics skills they missed by not being in school. After one year of participating in an AE program, most students take a placement test and re-enter their local public school at the second-, third-, or fourth-grade level.

Mariam’s parents enrolled her, and one year later, Mariam is thriving in fifth grade. She has dreams for her future, too.

“I would like to become a doctor,” Mariam says.

Around the world, an estimated 262 million children and youth are not enrolled in school for reasons ranging from conflict to poverty to perceived ability. And for every year that a child remains out of school, the chance of that child ever reentering formal education grows slimmer. Gaps in basic knowledge widen. Children become too old to reenter the grade that they left. Responsibilities at home become too great.

Prioritizing essential skills

But ERSA is showing that AE programs can help children overcome these barriers, even in regions where conflict has not fully subsided. Since 2015, the program has reached 10,150 formerly out-of-school children, and has reintegrated 7,460 of them into formal classrooms in the Gao and Menaka regions.

“Accelerated education has been around for about 25 years,” says EDC’s Brenda Bell, who has helped develop AE programs in Liberia and Mali. “But over the past decade, interest in it has grown. This is a direct response to the huge number of children and youth who are not in school, and who might want to enter or reenter the formal education system.”

According to Bell, well-designed AE programs do not attempt to condense an entire primary school education into a single year—a practice she describes as “cramming stuff into the box.” Rather, they prioritize essential skills and capacities that children need to succeed, including building foundational literacy and numeracy skills, as well as social-emotional competencies, such as tolerance and personal resilience.

“There’s less memorization and more application,” Bell says.

In ERSA classrooms, students sing, read aloud, learn by interactive audio instruction, and work together to solve problems. Overseeing the lessons are ERSA-trained facilitators—usually adult volunteers from the local community—who use a standards-based curriculum built specifically for the Malian context.

Emphasis on quality

Beyond individual success stories, such as Mariam’s, there is evidence that EDC’s approach to accelerated education is working at scale. Across all ERSA sites, three-quarters of enrolled children successfully complete a full year of accelerated education. And in communities where students are able to transition to a public school after their year in ERSA, 90 percent do. ERSA students also display significantly better literacy results than their peers who attended public school continuously.

“We emphasize quality so that children are able to transition successfully after their year in accelerated education,” says EDC’s Christina N’Tchougan-Sonou, director of ERSA. “Our goal is to make the transition into formal school more fluid, and to that end, we include community members and teachers from the formal school on the jury that evaluates each child.”

However, ERSA staff do encounter parents who are skeptical about enrolling their children. Some are dismayed by the quality of the local public schools, many of which are under-resourced, overcrowded, and without basic sanitation, making them unsafe or unwelcoming spaces for some students. ERSA is addressing some of these issues by transferring new classrooms and latrines that were built for the AE programs to their host public schools, as well as training school directors and teachers in the pedagogical techniques used in the AE programs —improvements that raise the quality of education for all the students and teachers.

ERSA’s community liaisons also play an important role in convincing parents to send children back to school. Liaisons discuss the benefits of the AE programs, from the improved classrooms to the fact that children learn in French—the language of broader economic and civic opportunity in Mali. Often, liaisons can break down parents’ skepticism about formal education by asking a simple question: “Don’t you want your child to be able to read and write?”

“The way we present accelerated education makes the whole idea of formal education more approachable and valued by families,” says N’Tchougan-Sonou.