Building Scientific Minds

During CYS workshops, preschool teachers become learners themselves.

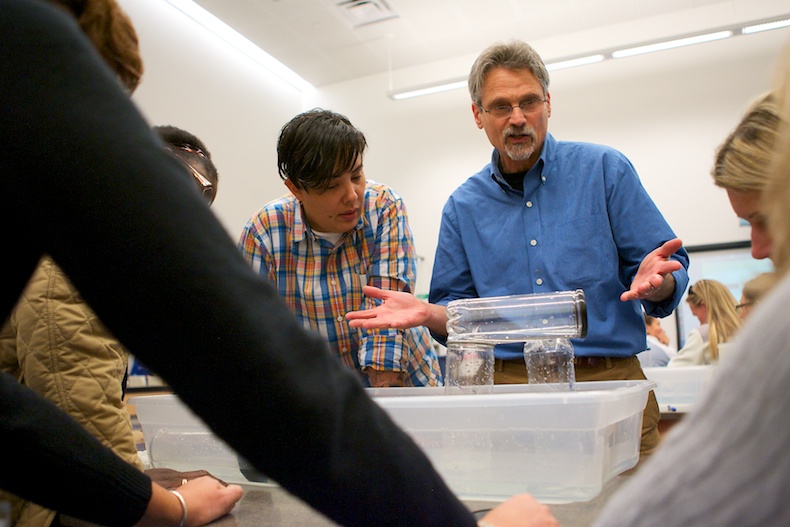

It’s not the students who are making the mess today. It’s the teachers.

Twenty-six of them are gathered around long tables in a science laboratory at the Connecticut Science Center. They fill old tennis ball canisters with water and talk about air pressure, all the while observing whether the water drips, dribbles, or spurts out of a series of tiny holes drilled in the side. It’s serious business—that is, until someone moves a finger off a hole prematurely, sending a fountain of water down to the floor. Everyone breaks down, laughing. There is water everywhere.

Cleanup aside, this is fun for the adults, who get to be learners instead of teachers for a change. It’s all part of an EDC professional development program called Cultivating Young Scientists (CYS), which is helping teachers bring authentic scientific experiences and experiments into preschool classrooms.

EDC’s Cindy Hoisington, a science education expert and one of the CYS workshop facilitators, believes that there is a big need for such a program. With studies showing that an early interest in science is a good predictor of a career in the field, CYS helps preschool teachers—who may not have much experience teaching science—spark curiosity among their young students.

“One of our strongest beliefs is that teachers need to build their own knowledge—especially preschool teachers,” says Hoisington.

And the mess the teachers have created at the water table? That’s part of the plan.

“We’re trying to teach the same way we want them to teach,” says Hoisington. “It should be a very parallel experience.”

According to the teachers participating in the program, the hands-on approach is working—and the skills learned in the workshop are transferrable to the classroom.

“I’m definitely learning how to refocus my attention on the water table,” says Paula Love, a preschool teacher at the University of Hartford Magnet School. “Before, it was just a play center. Now I’m trying to be more purposeful with it.”

All of this is music to Jeff Winokur’s ears. He co-teaches the CYS workshop with Hoisington and knows a lot of learning can occur at the water table—if teachers know what to look for, and if they know what questions to ask.

“We knew that many teachers had water tables in their classrooms, but we also knew that they could do so much more with them,” he says. “Teacher observations are important, and modeling that curiosity is worth its weight in knowledge”

Mayra Pino, a teacher at Catholic Charities Preschool, agrees. She’s noticed that since she began implementing this approach in her class, her students have been more interested in playing with bottles, tubes, and cups at the water table.

“My water table used to be an area where I would just send kids who needed to be busy,” she says. “Now it’s so much more. They come up with so many things to do.”