3 Ways to Support People with Substance Use Disorders during COVID-19

For individuals struggling with substance use disorders, the current COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic is a particularly challenging time. Quarantine and social distancing can lead to social isolation, and many counseling and support group networks have also been interrupted as a result of the pandemic. In addition, opioid and methamphetamine use impacts lung and heart function, putting people who use drugs at a higher risk of health complications from COVID-19, a respiratory illness.

Against this backdrop, community-based organizations serving these populations have a significant—but essential—task. How can they continue to support the health needs of people with substance use disorders in such a difficult time? Here are three tips from EDC’s Rachel Pascale and Noreen Burke.

1. Make treatment and medications more widely available

For people in treatment or recovery, access to medication-assisted treatments, such as methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine, is critical. But these medications are often prescribed by nurses, who are increasingly needed in the fight against COVID-19.

In response, some states—including Massachusetts and Pennsylvania—have started to allow pharmacists and pharmacy interns to administer medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) or for teams to conduct virtual assessments. In Massachusetts, health care organizations have begun conducting intakes for medication-assisted treatment over the phone or via a videoconference.

“Patient safety and health should of course remain paramount, but this sort of flexibility is really important right now,” says Pascale, a training and technical assistance specialist with Prevention Solutions@EDC.

There are other ways prevention specialists can support making treatment and medications more widely available in their own communities, says Pascale, including local advocacy efforts.

“You should advocate to your governor or health commissioner to increase the length of prescriptions for persons who rely on MOUD and are stable in their recovery,” she says. “You can also advocate for increasing the number of people who can take home their MOUD prescriptions.”

2. Explore alternatives to in-person contact with clients

With home-based and in-person meetings no longer feasible because of social distancing protocols, it is important for prevention and harm reduction specialists to consider alternative ways to meet with clients.

Burke, a substance misuse prevention specialist at EDC, says that telehealth should be considered as a viable method of communication, as well as social media for staying in touch and delivering health and safety information.

“Many states are passing emergency mandates for health care coverage to include all manner of telehealth,” Burke says. “This includes recovery coaches, many of whom are now conducting video and phone call outreach with their clients.”

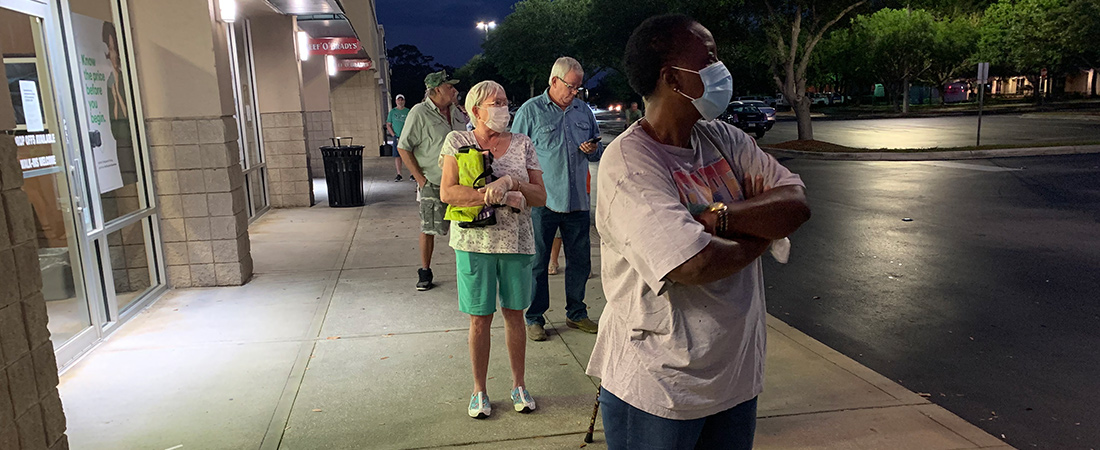

While telehealth is a good substitute for in-person meetings, prevention outreach specialists sometimes need to deliver naloxone or other life-saving items to their clients who still actively use. Burke points to the greater New Bedford area, where post-overdose response teams set up an outdoor drop-in center with supplies and food in to-go bags, facilitated the delivery of naloxone, and shared naloxone trainings via Zoom, the Web conferencing software.

“Drop-in centers where clients can pick up care packages while observing social distancing protocols are a good interim strategy to stay connected with vulnerable populations,” Burke says. “But I’ve also heard of some sites who are hand-delivering these supplies to the doorsteps of those who need them.”

3. Educate, educate, educate

Education is already an important component of harm reduction, but during this pandemic, it is especially important to help people who use drugs to learn how not to pass on the coronavirus, says Pascale.

“In practice, this means reminding people to avoid sharing drug equipment such as e-cigarettes and bongs,” she says.

Pascale adds that the COVID-19 pandemic will also disrupt the lives of people who use, even if they do not get sick from the virus. For example, shortages in the drug supply may occur, or emergency services may be slower to respond to an overdose because existing systems are stretched thin.

For these reasons, she recommends that practitioners distribute more naloxone, and that they help clients who use be prepared in the event they experience withdrawal symptoms.

“This is definitely a time when people with substance misuse disorders need extra support,” says Pascale. “We can’t forget about them.”